16

16

Linen Class Leads to a Textile Discovery...and a Mystery

by Lilo Bowman

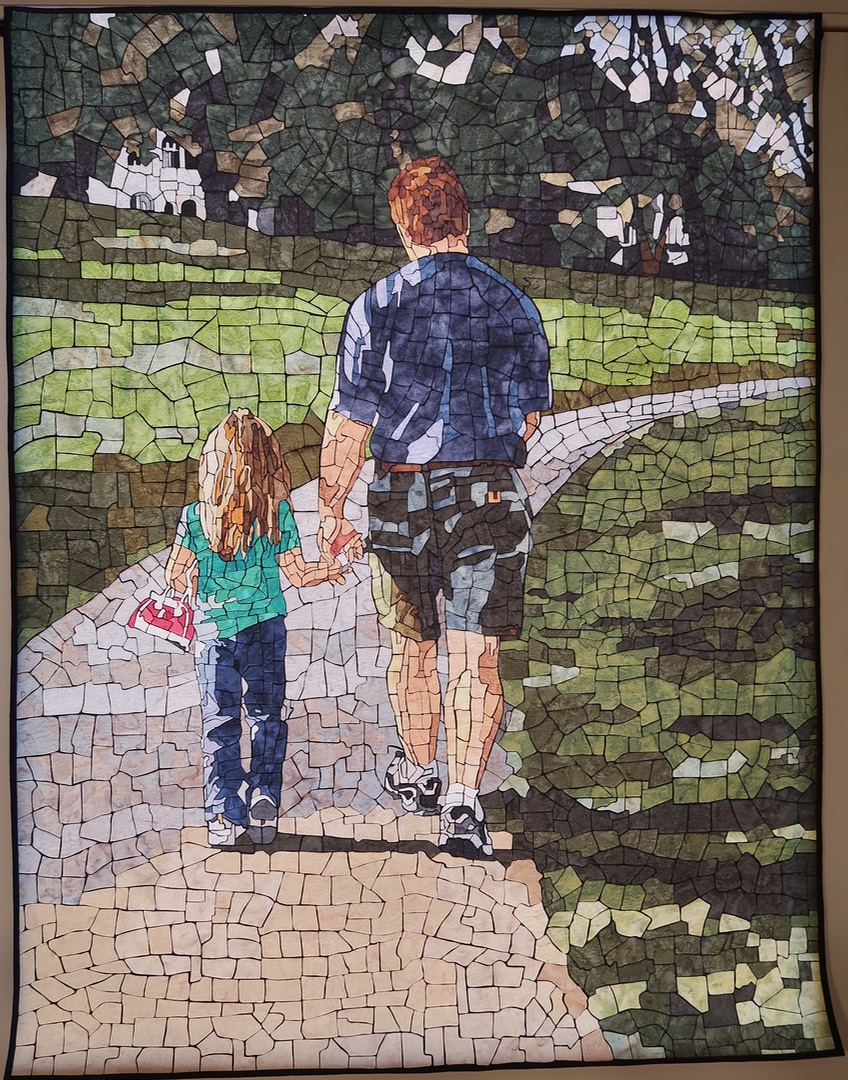

Courtesy of Cindy Needham

Nowadays, most of us don't use delicate linens and other textiles on a daily basis. However, while styles and tastes have changed over the years, many of us have collections of these lovely items--often family pieces--that we can't bear to toss out or give away. Usually these cherished textiles stay tucked away and are viewed only on rare occasions. What a shame!

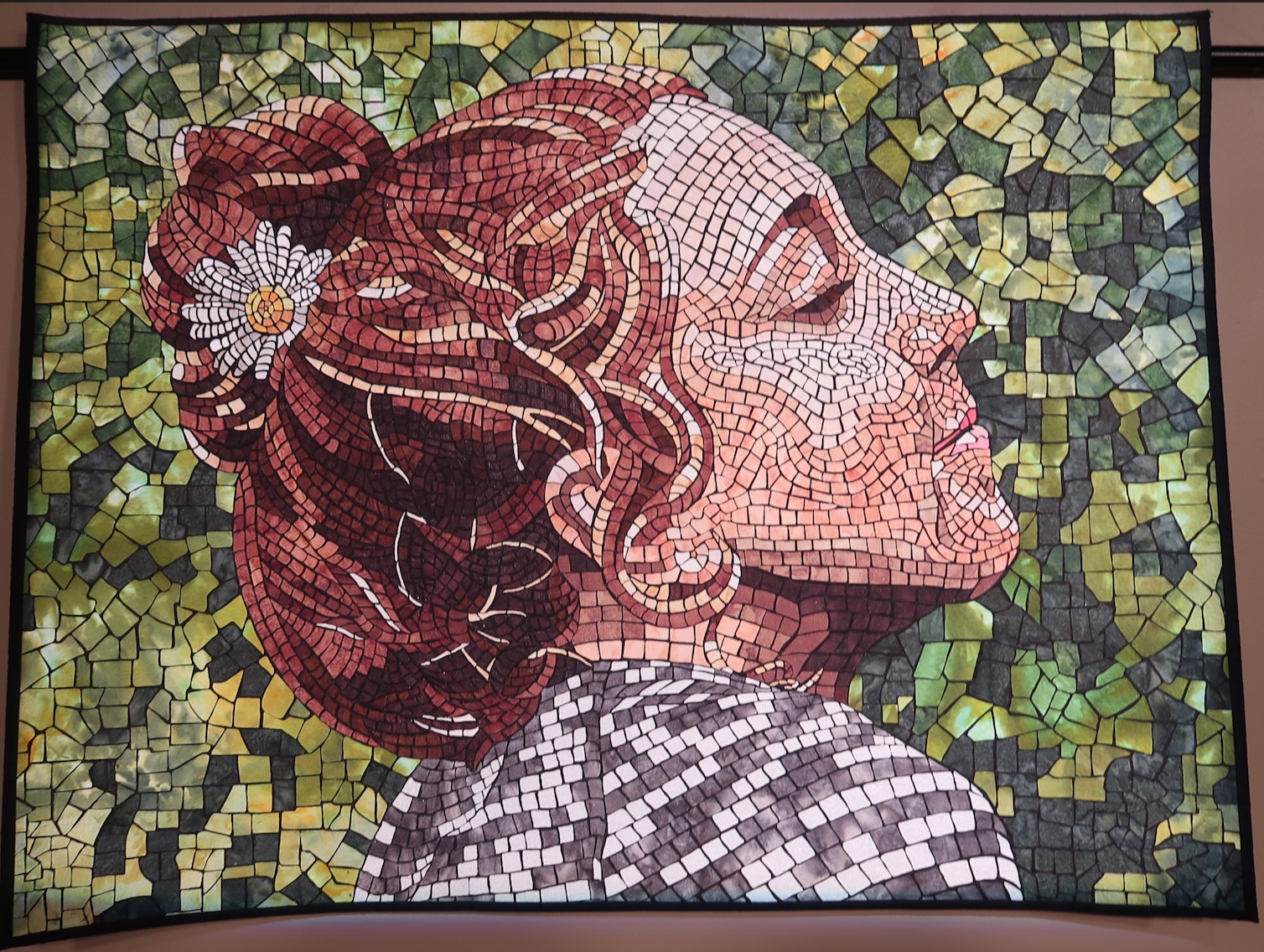

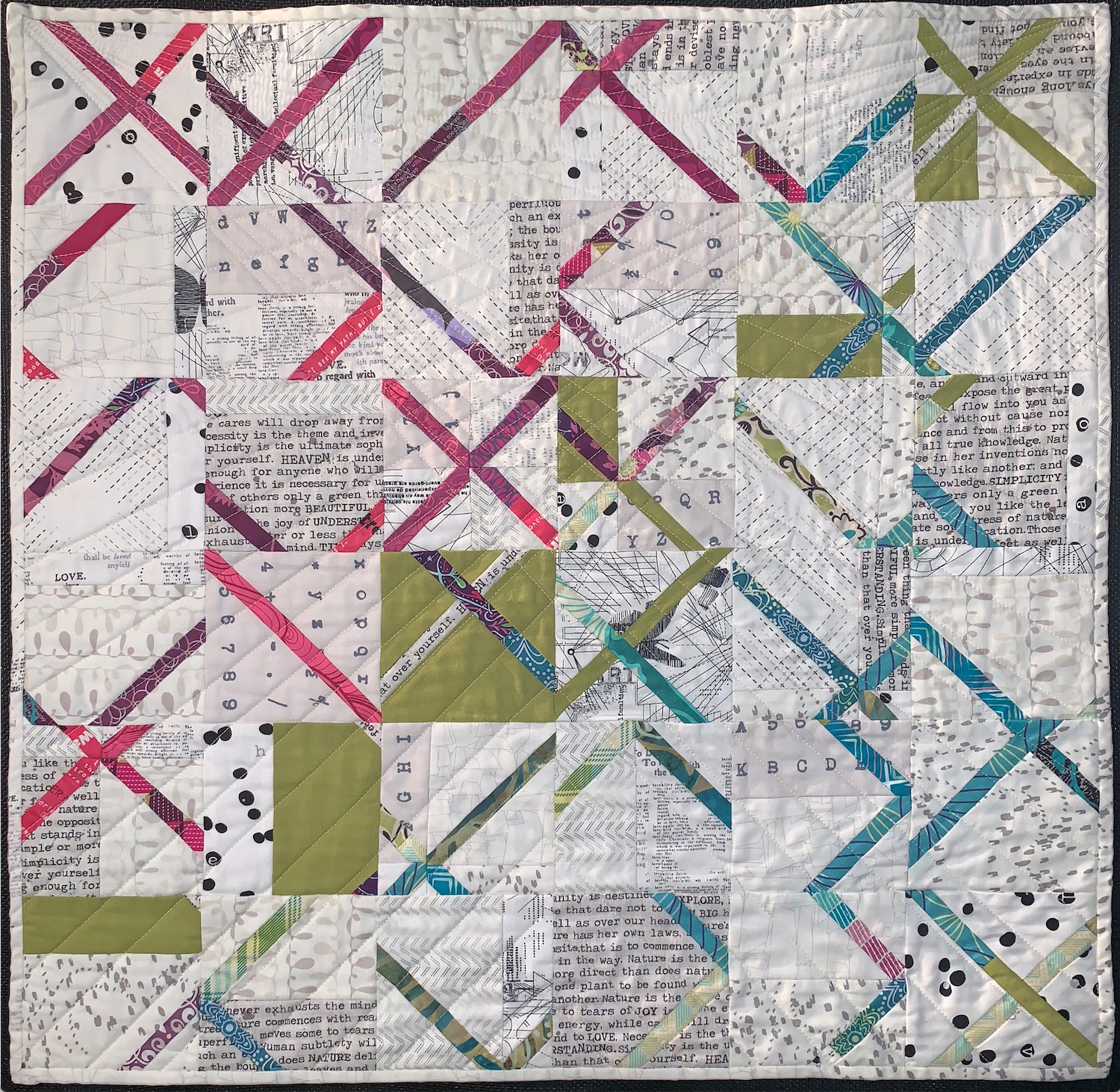

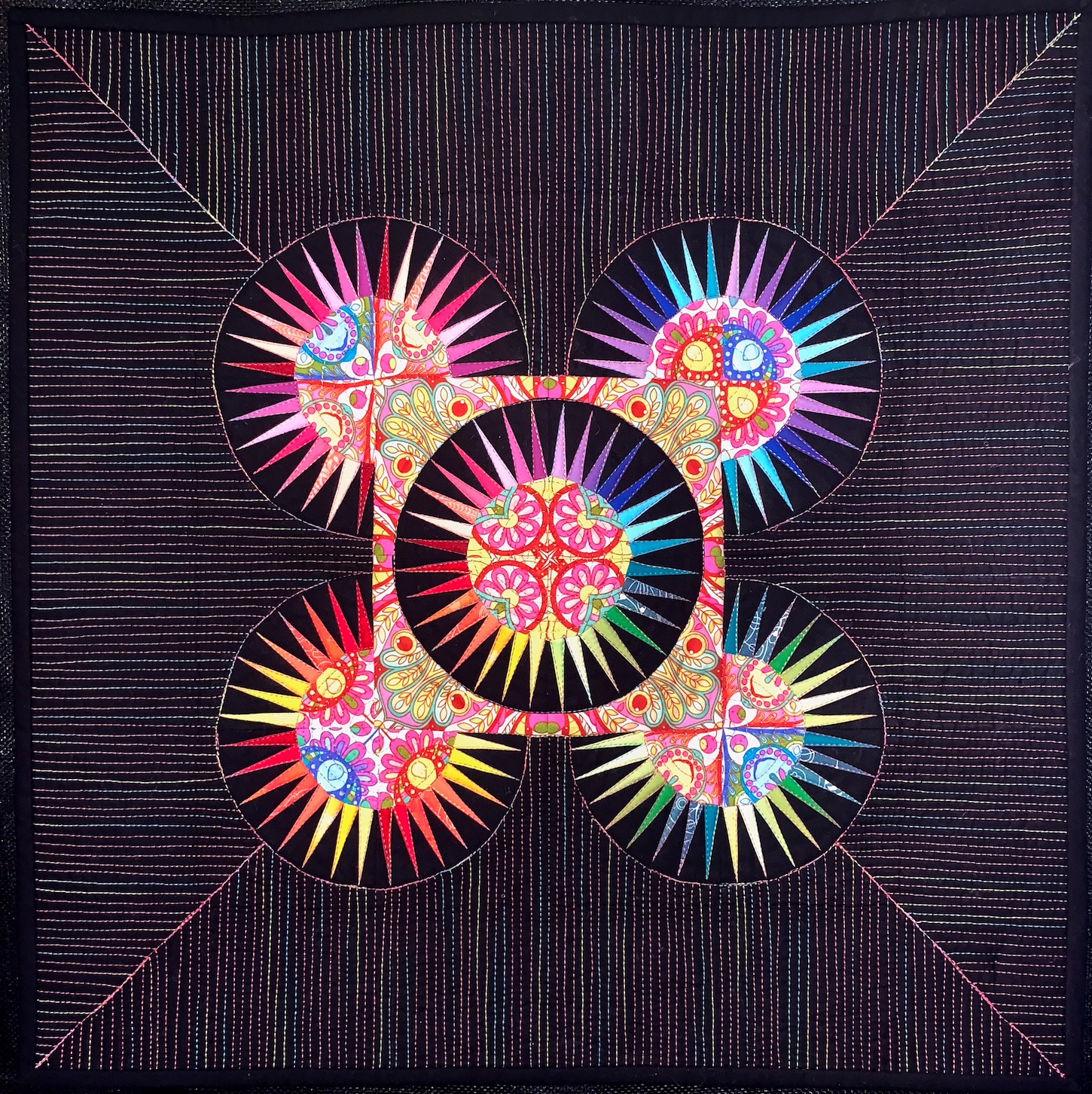

Recently I had the opportunity to take a "Linen Ladies" workshop with Cindy Needham. Cindy is a quilter known for taking useable pieces of beautiful antique textiles and giving them new life in a quilt. The vintage pieces are the "stars," but with Cindy’s beautiful handiwork, the new creation takes on a whole different dimension. According to Cindy, the idea is not to overpower the original maker's beautiful work, but to showcase and incorporate the old with the new and give life to the piece in a way that can be passed on to future generations.

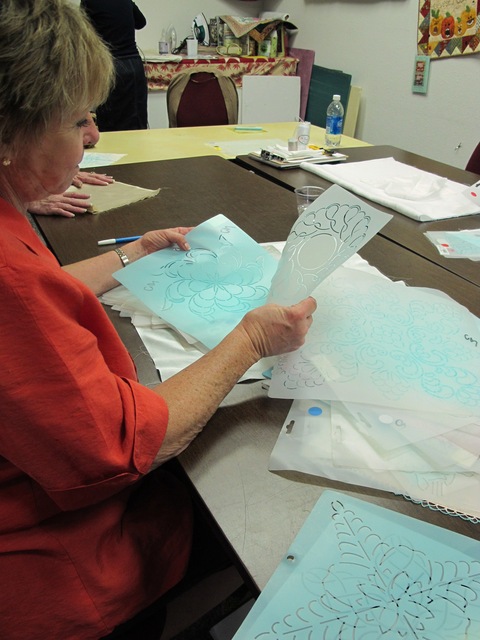

Class participants were asked to bring old linens to be audition as potential "new" works. As the students began revealing the treasured pieces that they had brought from home, there were many "oohs" and "aahs" heard around the classroom. It was fun to walk around the room and hear each person share the story behind the pieces she had brought. Many were family pieces that had been saved, as expected, in a drawer for many years.

As the class got underway, Cindy began sharing the unique challenges and pleasures of working with antique textiles. She covered a variety of topics, including how to deal with stains and holes, and the selection of marking tools, threads, peek-a-boo fabrics (that is, the foundation fabrics for the vintage pieces), batting, and beads. While covering these topics, Cindy frequently used completed pieces as examples. It was during the discussion of peek-a-boo fabrics that Cindy unveiled a piece that caught my eye immediately. It was a small piece, about 15" square. The center motif featured a doily centered on a small napkin, with a beautiful lace edging along the outer border.

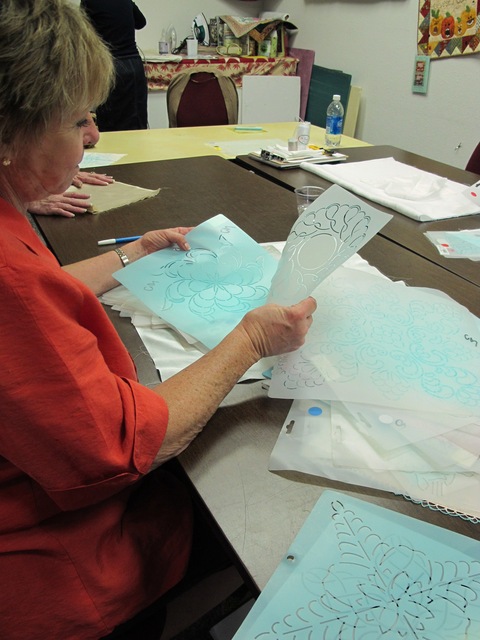

Students sort through linens.

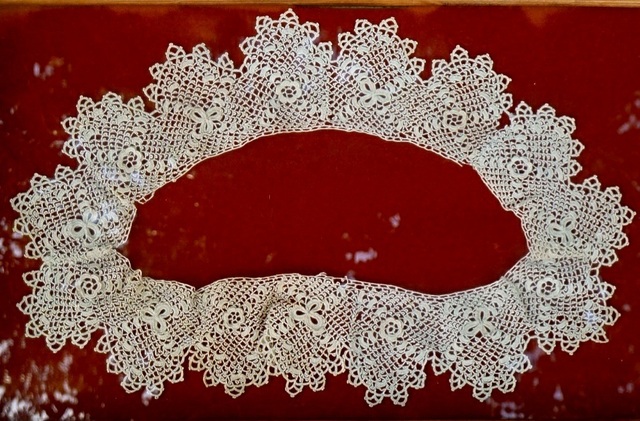

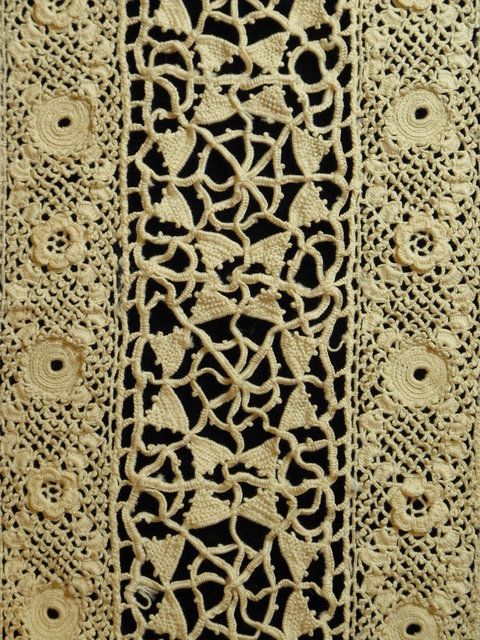

Detail of Irish crochet lace. Courtesy of Cindy Needham

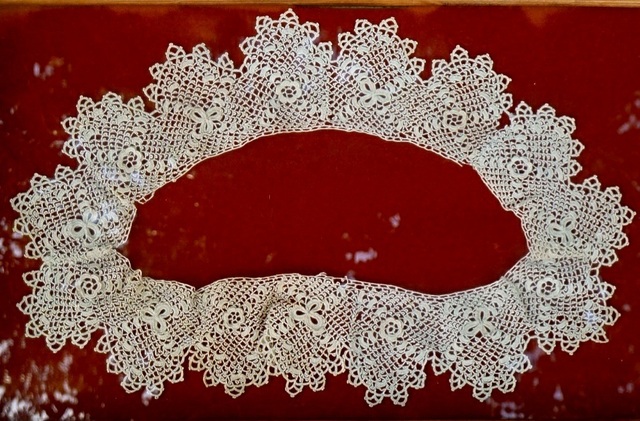

Not only was Cindy’s completed piece stunning, but I remembered that I have seen this particular type of lace edging before…in my parent’s home!! I recognized the lace immediately as Irish crochet lace! For years, my mother has had a collar (photo below) that belonged to her sister, framed and hanging in the living room. She believes that the collar was made by her great-great-grandmother, who came from County Cork, Ireland. I had heard the story about the maker, and that the Rose and Shamrock design was unique to the work made in Ireland during the nineteenth century. What I didn't know (until I began my research) was that lace making was taught to young girls by the nuns as a way to help desperate families during the time of the potato famine.

Irish crochet collar worn by Lilo's aunt as a child. Courtesy of Melinda Burt

The 1800s in Ireland was a time of great difficulty for the many tenant farmers living on small parcels of land called crofts. The most productive land was used to grow crops for the landlord. Any remaining land would provide food for the farm families. Although some were able to include other items such as grains and assorted vegetables, rocky soil and restricted land meant that most families grew potatoes as their staple source of nutrition. When the potato blight of 1845 and 1851 struck, thousands of tenant families found themselves without food or any means of earning an income.

The Ursuline nuns, who had been in Ireland since 1771 and were greatly involved with primary- and secondary-school education, searched for a way to help the starving families. Using the Venetian-needle tradition of lace making (which the nuns had brought with them from France) as a starting point, they opened “crochet centres” throughout Ireland. The first of these centres was established in 1845 in the Convent at Blackrock in County Cork. Other communities soon followed. “And so crochet, which originally had been deemed ‘nun’s work’ in the convents of Europe…changed and developed a unique style, which became, for Irish people, a symbol of life, hope and pride. In the years immediately after the famine, crochet became a practical subject in the curriculum of convent schools.” (Excerpt from Irish Crochet Lace Exhibit Catalog, Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA)

Venetian-needle lace making was a highly skilled and labor-intensive art, often requiring hundreds of hours to create one small piece. Enter Mademoiselle Riego de la Blanchardaire, born to a Franco-Spanish father and an Irish mother in 1820. Mademoiselle discovered that traditional Spanish needle lace (which looked very similar to Venetian needle lace) could be converted to a crochet hook with very similar results achieved in less time. Using Mlle Riego’s instructions, the nuns were able to teach girls in the schools how to create lace that would then be sold. By 1847, some areas of Ireland employed as many as 20,000 lace makers. In fact, girls at that time were considered more valuable than boys, as they could offer a family income as a result of their lace making. Often boys cleaned house while the girls sat and stitched.

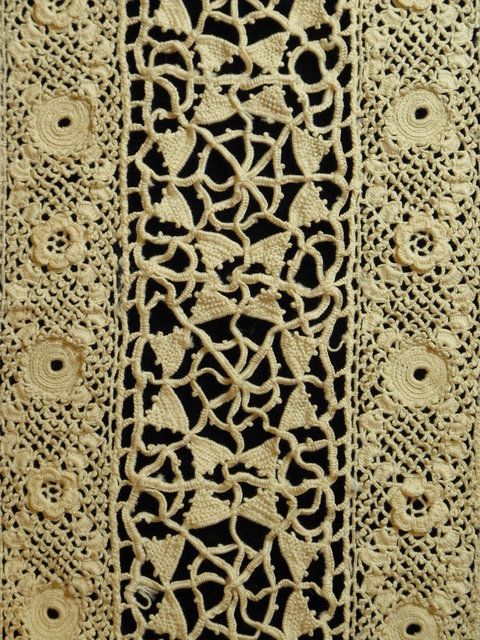

Blouse insert featuring Irish Crochet lace. Courtesy of Lilo Bowman

In addition to teaching lace making, the nuns (very smartly) began adapting design elements from Venetian needle lace, Honiton lace, and Flemish lace. By 1850, Irish crochet lace had evolved as an art form on its own merit, and was highly desired in the most fashionable cities, including Paris, Vienna, Brussels, London, and New York. On the day of her wedding in 1840, Queen Victoria wore a veil made of Irish crochet lace. Throughout her reign, she wore lace, fueling a worldwide craze. Wealthy tourists traveling through the region known as “The Prince of Wales Route” (Killarney to Glengarriff) often would stop at the convent to purchase lace for themselves or as a souvenir. (This fact posed a question from Cindy when she shared a large French-lace tablecloth WIP (work in progress) that she had purchased recently on eBay. More on this in a bit.)

Detail of blouse insert. Courtesy of Lilo Bowman

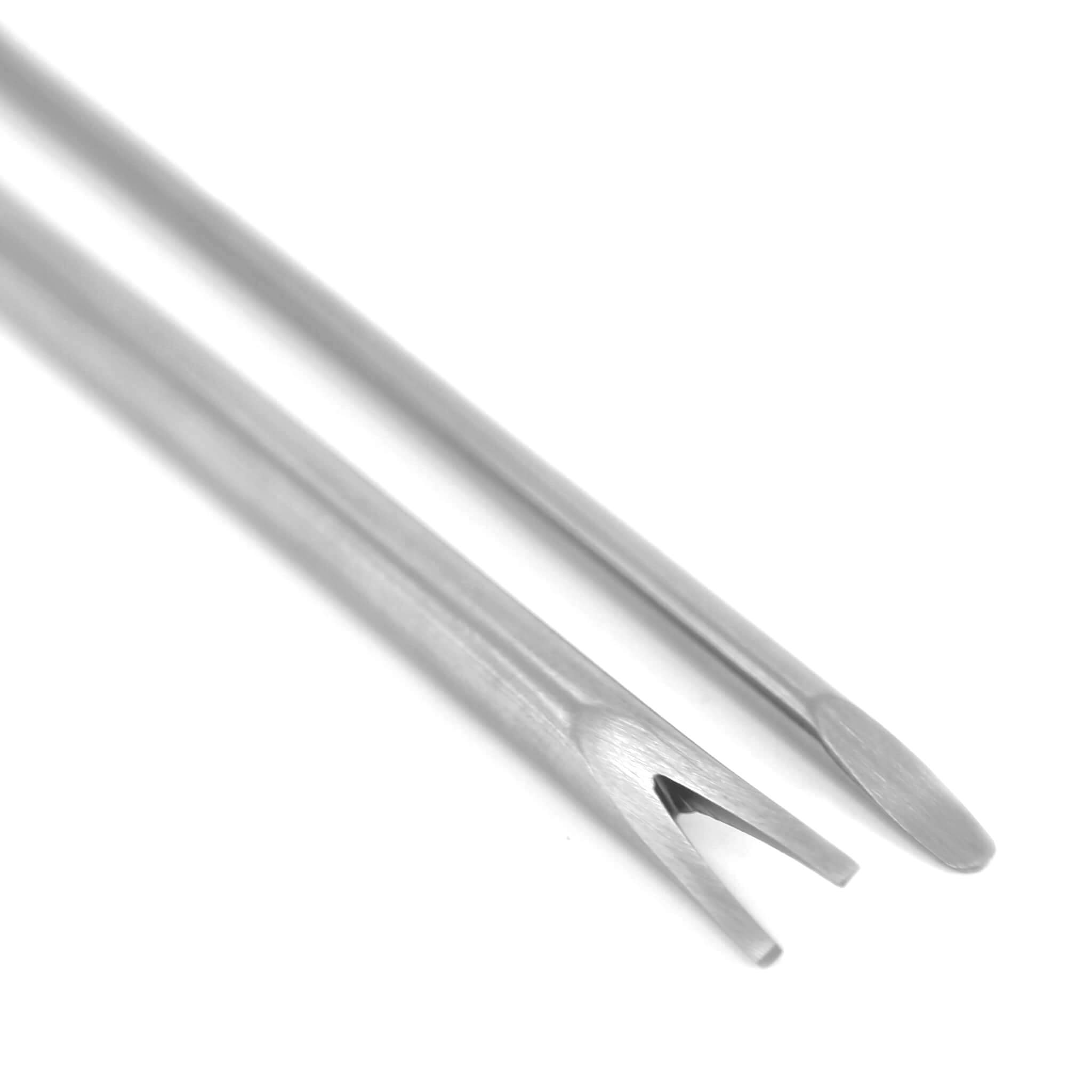

“Irish crochet lace is worked with a very small fine steel hook with a handle of bone, cork or wood. The best crochet lace is always very firmly and evenly worked. Numerous sprigs representing leaves, flowers, etc. are worked over a foundation cord. These solid pieces are arranged and firmly tacked onto a foundation pattern. The spaces between the sprigs are then joined by crochet bars. The complete piece of lace is then finished off with one of the edgings characteristic of Irish crochet lace. In working the sprigs, the cord padding is an important factor as its tightness or slackness allows stems or leaves of the various designs to be artistically curved in any desired direction." (Excerpt from Irish Lace Museum). This allowed for a great deal of creativity on the part of the maker.

As entire communities were often illiterate, patterns and designs were shared orally or in simple design books. It was said that a skilled lace maker should, after careful study, be able to replicate a design motif from a sketch. Those with less skill worked simpler elements. Often whole families were involved in the making of a lace piece. Those with less nimble fingers might work leaves or stems, while the more skilled would work on the more difficult elements. Finished pieces would be taken to the crochet centre to become collars or cuffs, or incorporated into dresses or other decorative pieces.

As factory production of machine-made lace became more prevalent and affordable, the cottage lace industry declined. There was, however, a brief resurgence in the 1880s. Many of the family heirlooms that we see today are from this time period.

Deciding on a quilting design takes time. Student marks an antique hankie for quilting.

Cindy is often surprised by viewer’s reactions to her work. Sometimes she is scolded for "mis-using" a piece. While she wouldn't attempt to use a museum-quality piece in her work, she does think that it's fine to use lovely pieces such as a tablecloths, doilies, dresser cloths, and so on. The original maker spent many hours--often weeks--working delicate designs by hand. Why not showcase this wonderful work for the next generation to admire and appreciate?

So, the next time you're rummaging through your antique linens, why not think about giving a second life to a favorite piece? Your family just may thank you for it.

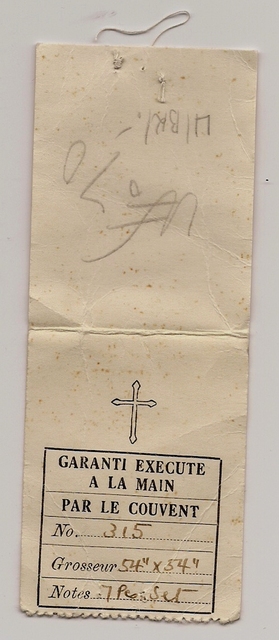

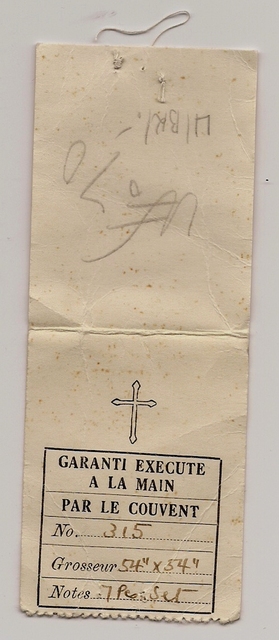

Back to Cindy’s eBay purchase: When the lace tablecloth arrived at her home, she found that the original owner had never used it; the tag was still attached. The only information provided indicated that the piece was from France and that it was made in a convent. Cindy is very anxious to know more about this piece and those who created it. If you recognize the lace work, or know a good source for more information, please leave a comment.

To learn more about antique lace, visit these websites:

Kenmare Lace and Design Centre click here

Irish Lace Museum click here

Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles click here

.jpg)