13

13

Image courtesy of Teresa Duryea Wong

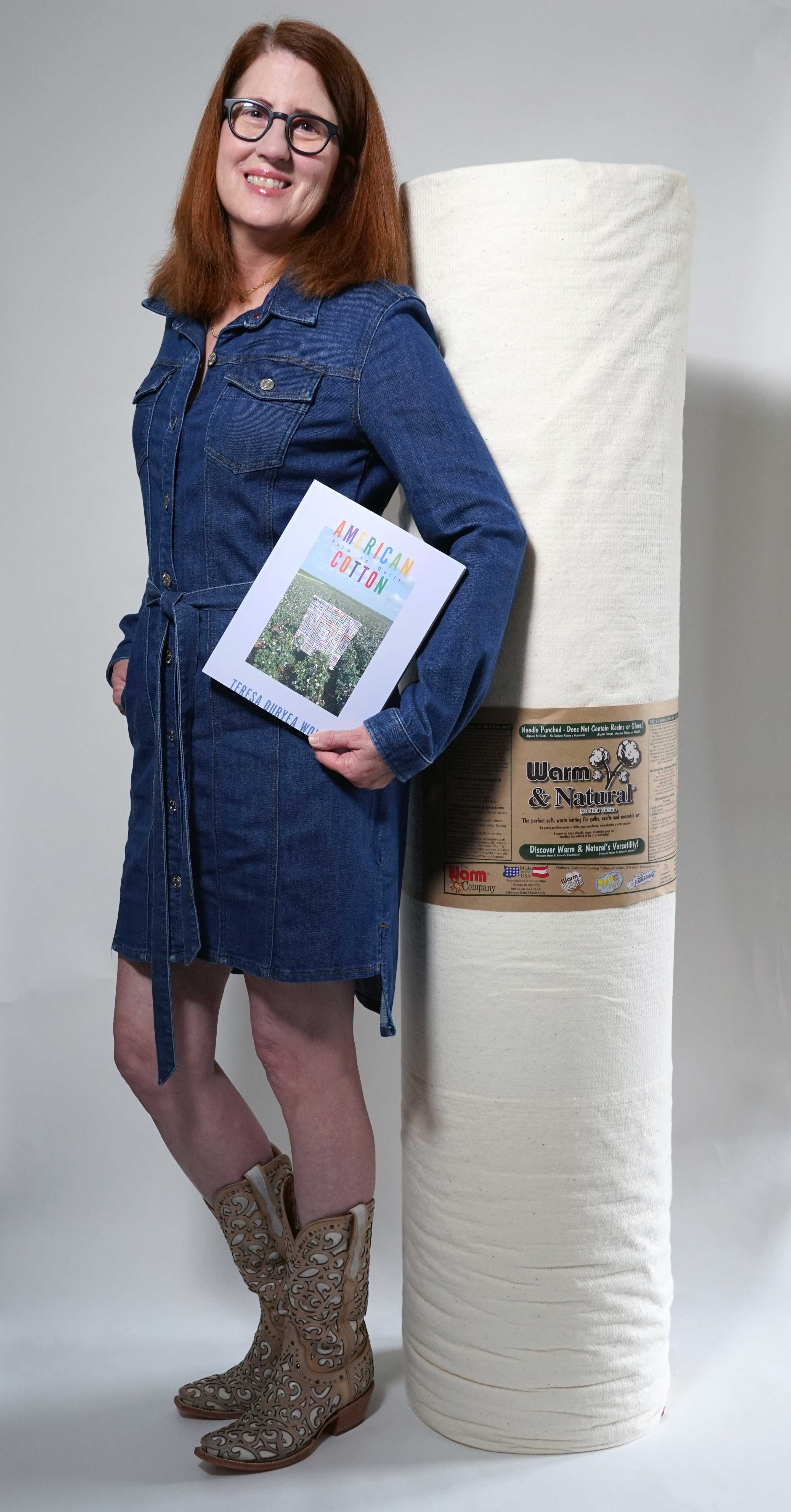

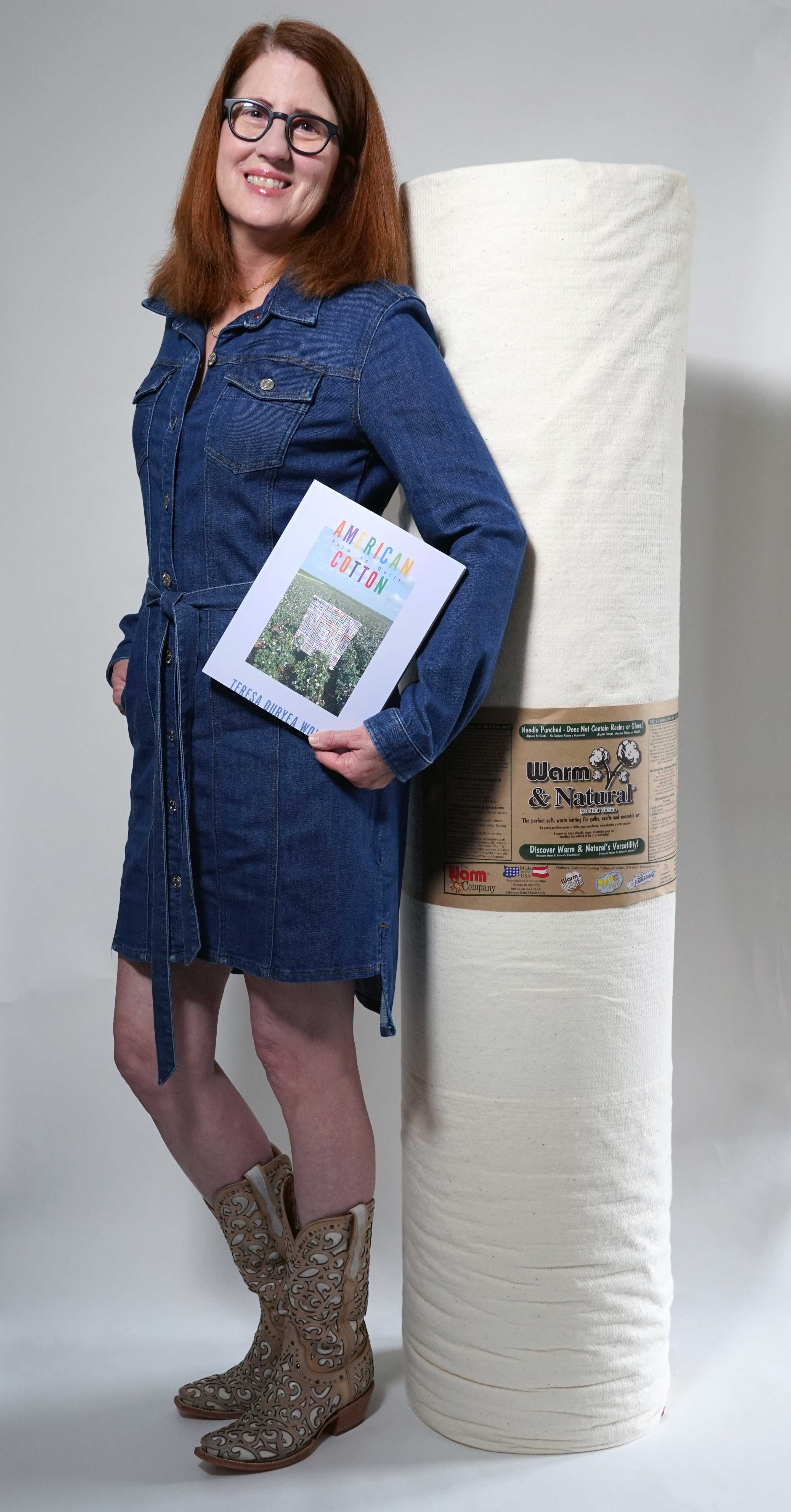

Teresa Duryea Wong has been a frequent TQS contributor (read more here and here) with articles and books focused on American and Japanese quilting. Always curious, Teresa's fascination with quilting cotton, led to several years of interviews, research, walks up and down hot and dusty farm fields to better understand what role cotton plays in the US economy, the farmers who grow cotton and the quilters who love working with this most beloved of fibers. American Cotton: Farm to Quilt is hot off the press and Teresa shares an insight into how your batting (you know, that yummy stuff that gives a quilt that, cuddle up and envelope me feeling?) is grown, harvested and processed for the shelves of a quilting shop near you.

Image courtesy of Teresa Duryea Wong

Heaps of King Cotton in Quilt Batting

An excerpt from “American Cotton: Farm to Quilt.”

by Teresa Duryea Wong

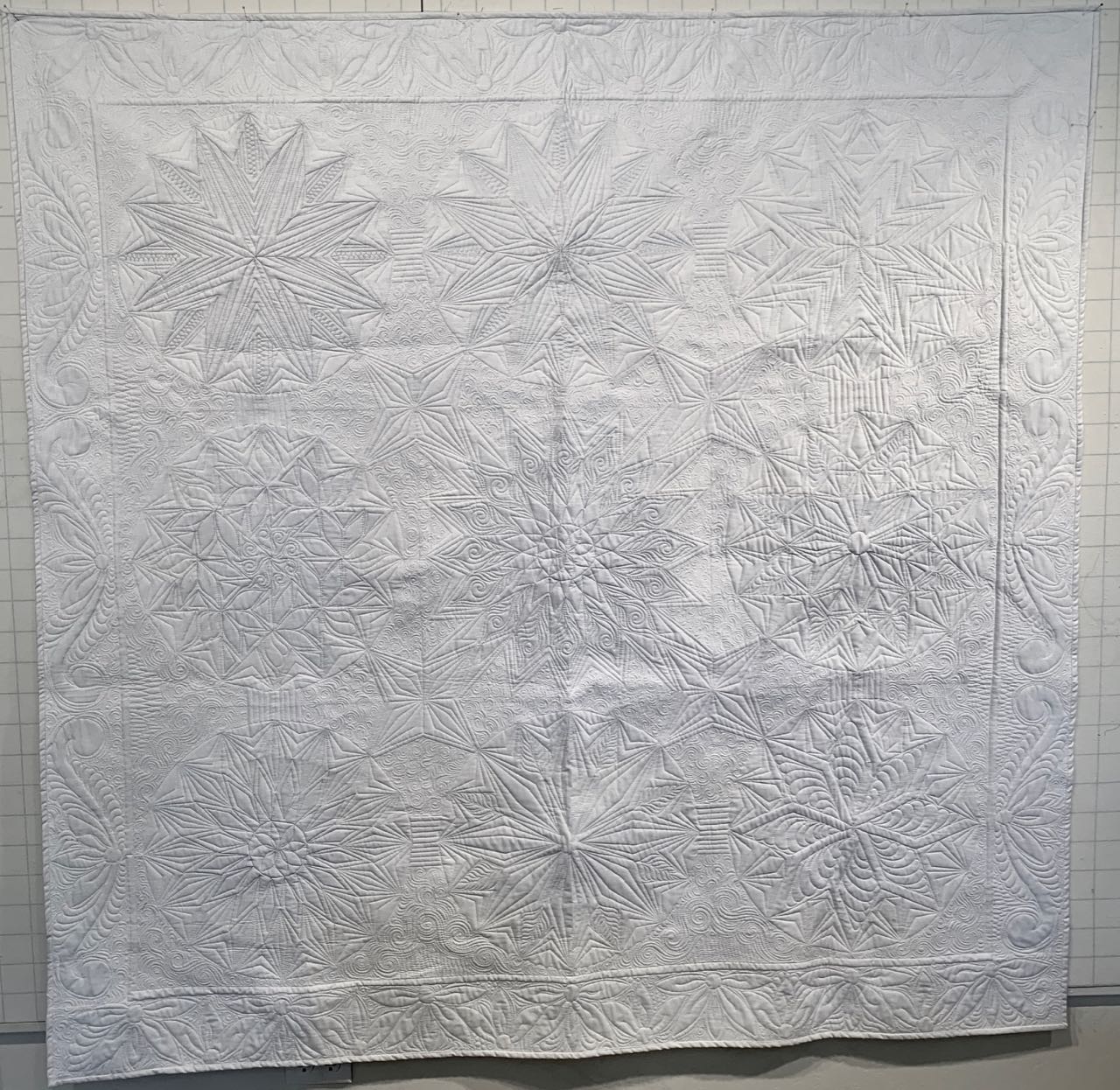

Quilts have been examined, copied, shared, preserved, destroyed, written about and researched for 200 years. Yet, there’s very little curiosity about the material between the two layers of fabric that make a quilt a quilt. Like a classic peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich, the layers of bread are important, but it’s the stuff inside that makes it yummy.

Quilt batting, or what used to be called wadding, is the soft, solid, yummy layer inside a quilt sandwich. The batting is what makes a quilt warm and gives it its drape, and today a quilter can find a batting in almost every make, shape, and material, whether thick or thin, to meet her needs. Besides cotton, other common quilt batting materials are wool, polyester, cotton blends and bamboo.

The process to make cotton batting is strangely very hi-tech, but also strikingly similar to the way it has been made for a century. I was fortunate to visit the manufacturing facility owned by The Warm Company in Elma, Washington in 2018, and it was fascinating to learn how the cotton travels through giant automated machines and comes out the other end as a smooth, finished product, ready for the billions of quilt stitches that will eventually pierce it.

(Half of America's cotton crop is grown in Texas. Photo by Steve Chapman)

Heaps of American cotton are purchased each year and turned into cotton batting for quilts, as well as industrial batting for furniture and bedding. The Warm Company alone, whose primary business is quilting, purchases four million pounds of fresh, American cotton annually.

To put that in perspective, it takes roughly 14,000 acres of West Texas farmland to produce four million pounds of cotton. That means the Warm Company buys enough cotton to cover the entire crop of at least four farmers, and they are spending approximately $3.2 million annually on those purchases.

The Warm Company has strict requirements for fiber length, thickness, strength, and color, and only the cleanest cotton is chosen. The raw cotton, which has been ginned to remove leaves, sticks, seeds, etc., travels to the Warm facilities where it is cleaned again, twice in fact. This super-fine cleaning process separates even more leaf or stick fragments from the fiber. It is natural for very tiny specs of leaf or stick to remain, even after all this rigorous cleaning. Those tiny specs are called pepper.

The pepper look is what you will see in the batting named Warm & Natural. This product is so popular with quilters that many consider it essential to quiltmaking.

Warm & Natural batting is not bleached, and as the name suggests, the batting has a natural-looking creamy, off-white color.

A second type of batting is made with purified cotton, and this is the cotton used to make Warm & White batting. With purified cotton, the individual fibers are scoured to remove natural oils and discoloration. The treatment involves a gentle bath of hydrogen-peroxide.

This process leaves the fibers so clean and white that the fibers actually become coarse, so a lubricant is added to the cotton, not unlike when human hair is bleached and needs a conditioner to make it soft again. The Warm & White batting is preferred by many quilters who seek that clean, pure snowy-white color.

After cleaning, the cotton begins its long journey through the conveyor-belt maze of automation that turns fibers into batting. The cotton fibers are formed into layers, and the layers are laid on top of each other. Eventually, a scrim is added to the layers of cotton fiber. A scrim looks a lot like a common dryer sheet, only it is significantly lighter and thinner.

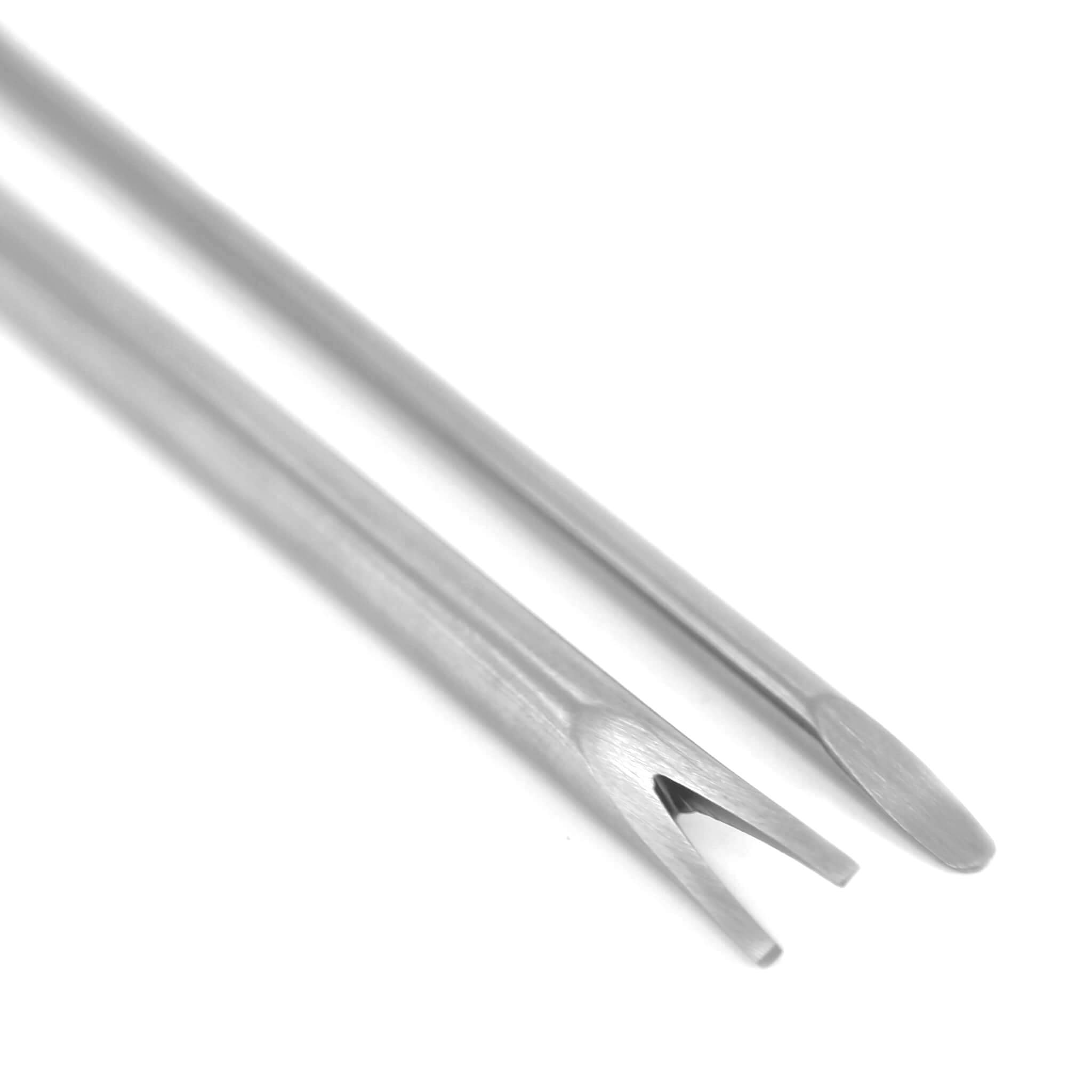

The fibers and scrim are needle-punched millions of times, in a matter of seconds, by very long needles. As the needles move up and down through the fibers, they force the cotton down through the scrim and back up again until the fibers and scrim essentially become completely intertwined.

Thanks to the scrim, the batting holds together and at the Warm Company, no glue is added. Stitches in most modern batting can be up to 10 inches apart without worrying about the batting moving or bunching up.

(Inside the Warm and Natural manufacturing facility in Elma, Washington, where every package of pre-cut cotton batting is folded by hand. Image courtesy of Teresa Duryea Wong)

Heaps of King Cotton in Quilt Batting is an excerpt from “American Cotton: Farm to Quilt.”

For more information, visit Teresa’s website

Books by Teresa Duryea Wong

American Cotton: Farm to Quilt

The story of the American cotton farmer,

America’s textile industry and their connection to quilting

Cotton and Indigo: From Japan

The story of Japan's cotton and indigo, and their

enormous contribution to fiber arts worldwide.

Japanese Contemporary Quilts and Quilters:

The Story of an American Import

The story of Japan love for American quilting, how

it came to be favorite pastime and an artform that now

has a uniquely Japanese esthetic.

When she's not busy writing, it's off to the post office to ship out more autographed copies of books. The life of the author is so glamorous!

.jpg)