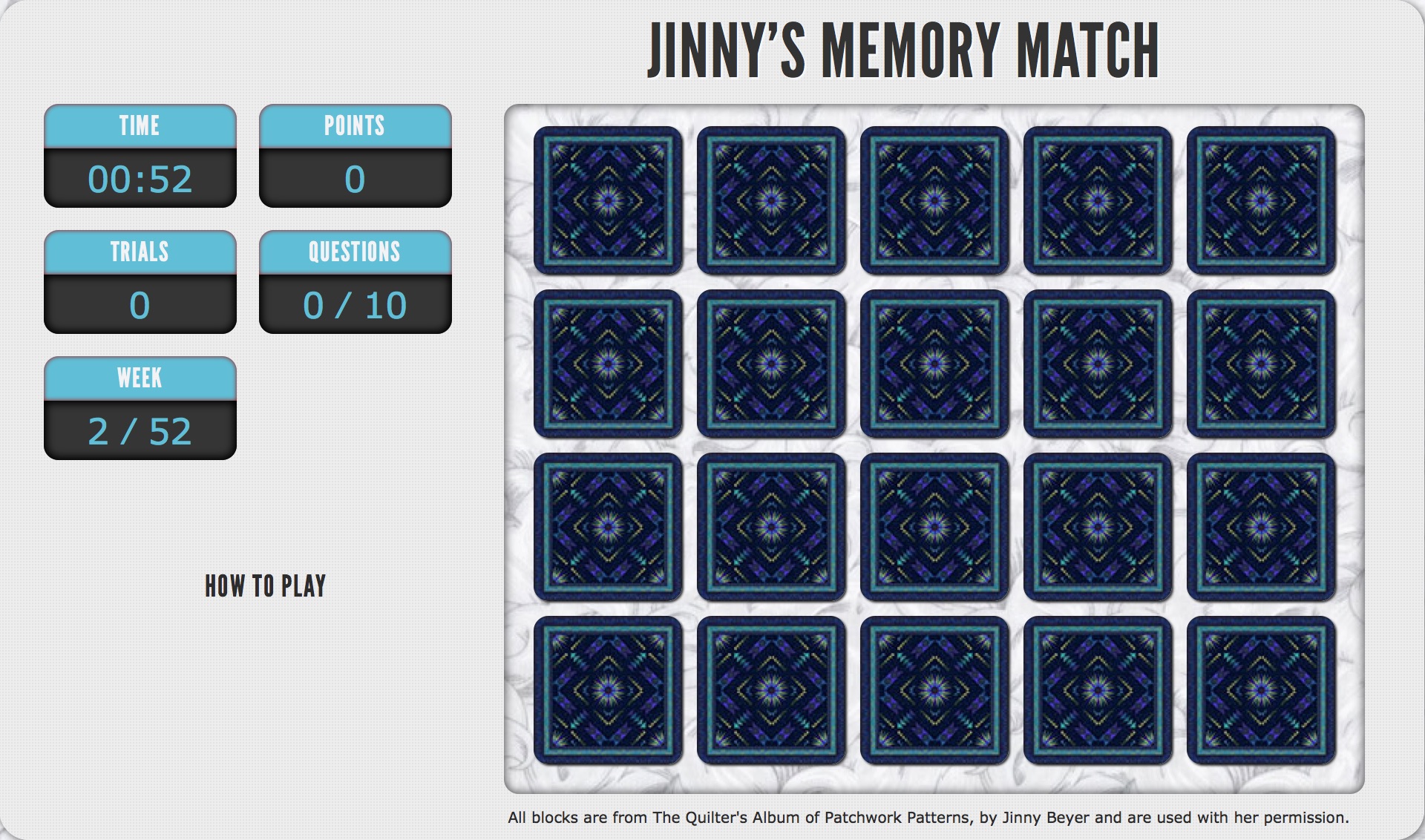

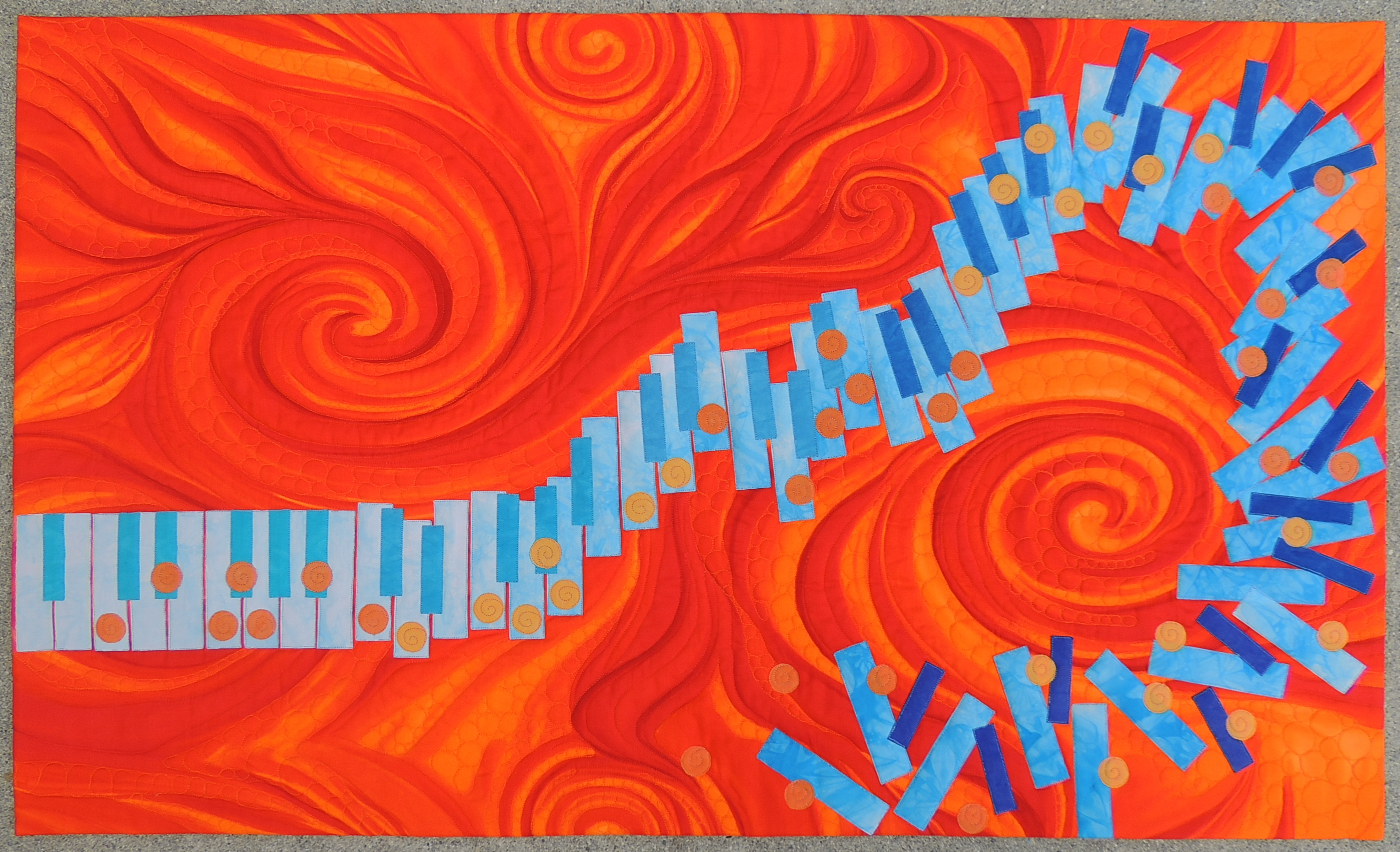

As we wrap up Principles of Design, we wanted to give you a chance to see how much you have learned over the last sixteen weeks. We have covered a wide range of subjects. Match the terms with the corresponding images below. If you are not sure, we have included a link to each term so that you may review the principles again. (We will give you the answers in next week's post.)

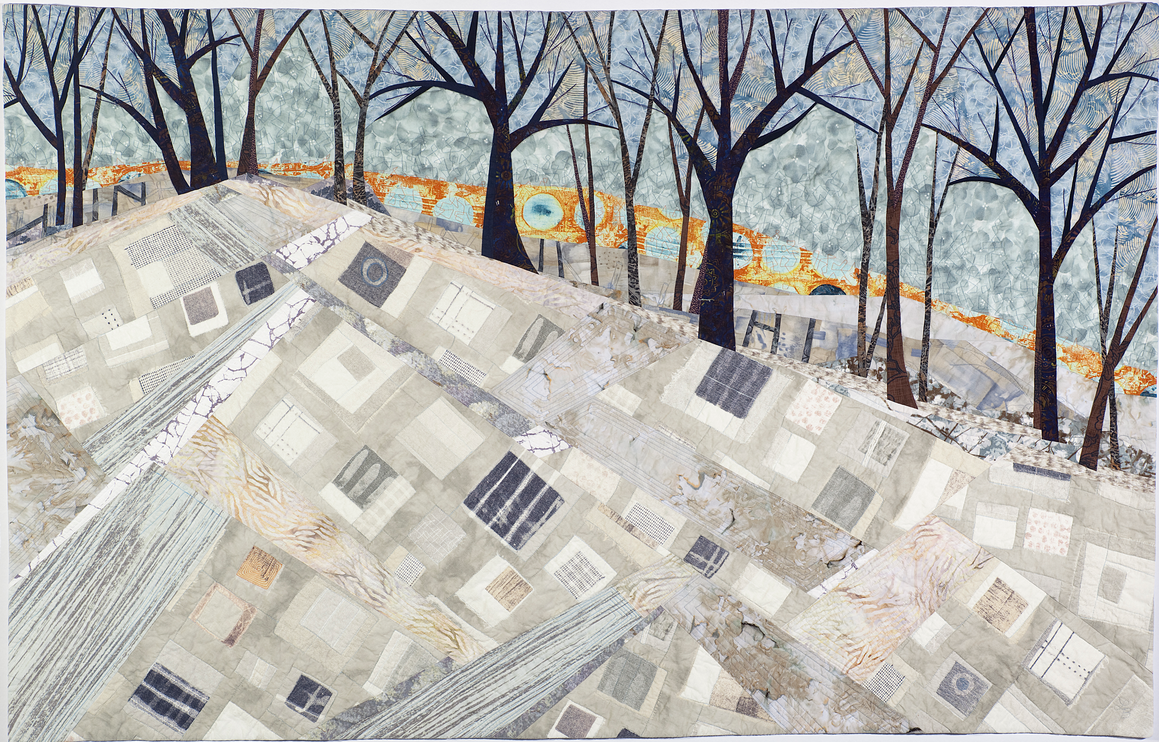

Rhythm/Movement - Week 39

Unity/Variety - Week 40

Contrast - Week 43

Symmetrical Balance - Week 32

Pattern/Repetition - Week 35

Emphasis - Week 38

Asymmetrical Balance - Week 33

We hope that you have enjoyed and benefited from our year of learning as it pertains to your own quilt work. Stay tuned for a sneak peek at our new 2018 year-long learning program in next Monday's newsletter.

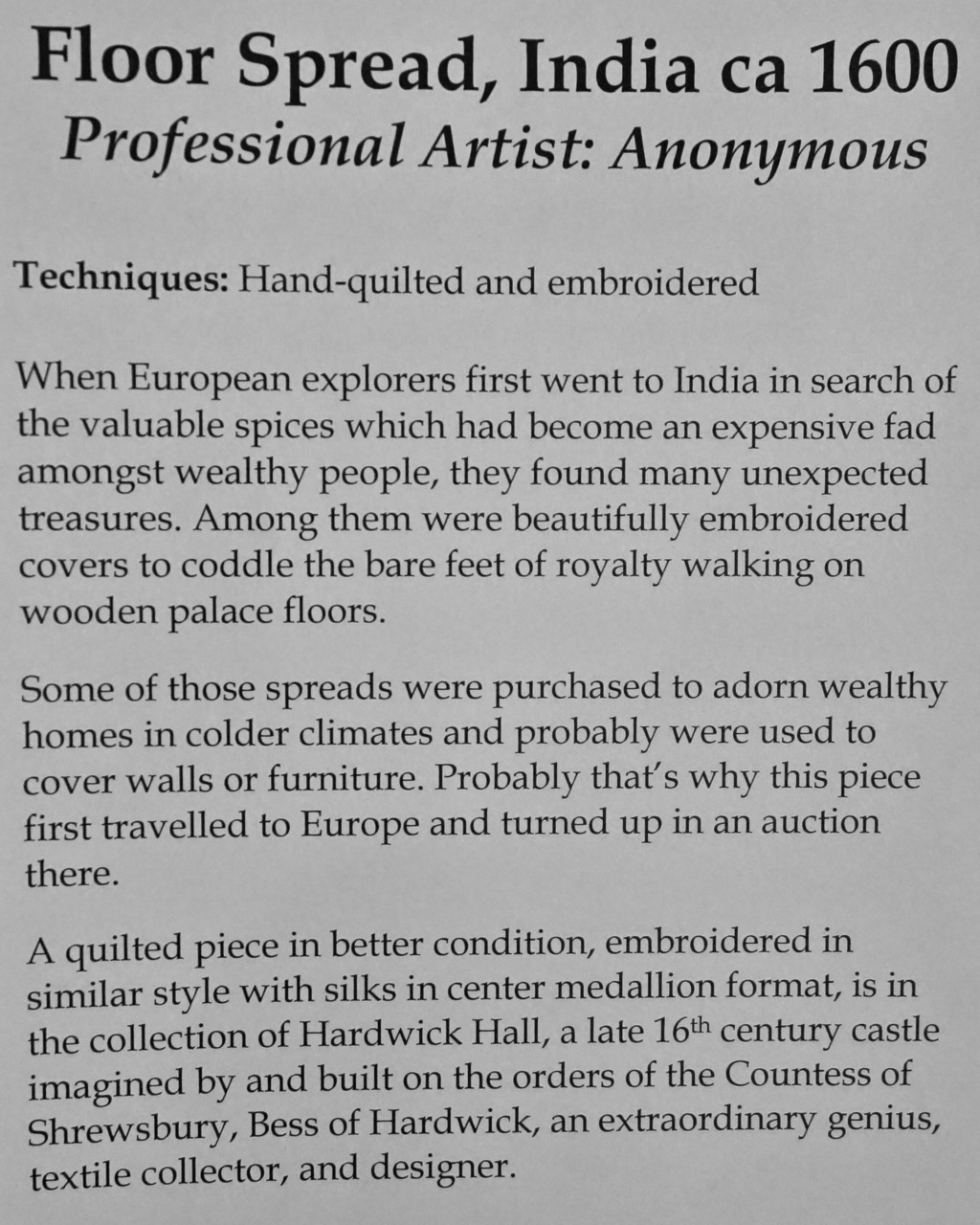

Cotton: A Very Long Journey

by Teresa Duryea Wong

You’re at the quilt shop, standing in front of rows and rows of fabric. Some bolts grab your eye immediately, begging for a closer inspection. Others, not so much. Whether the fabric speaks to you or not, there is a good chance most of that fabric in your local quilt shop is 100 percent cotton. And that cotton has been on a very, very long journey.

In fact, one tiny boll of cotton, from a seed in the ground, to a soft and strong fiber that is ultimately used to construct your favorite fabric, may have traipsed around the world two, three, maybe even four times before it lands on the shelf at your local store.

So, when you pick up that perfect fat quarter for a mere three bucks or so, consider this. Cotton is grown in some 80 countries. The cotton fibers inside your quarter-yard were most likely grown in China, India, Pakistan or the U.S., possibly even Texas, which is by far the largest producing state in the U.S. It’s also possible the cotton was grown in Brazil, Greece, or Australia.

The multi-billion-dollar quilt industry is one of the largest consumers of 100 percent cotton textiles. That is quite something to absorb. In the not too distant past, lots of things – clothing especially – were all made with pure cotton. But the evolution of technology has allowed countless combinations of synthetic textiles that enable clothes to be soft, strong, stretchy, structured, water/weather proof, etc. Not even blue jeans, which were once renowned for their use of cotton, are all cotton anymore. Instead, most jeans are now constructed with a blend of fibers and/or synthetics. That said, in the past few years some high-end blue jean manufacturers are returning to their roots and touting their “new” jeans made with pure cotton.

Today, quilting fabric stands nearly alone in the world of 100 percent cotton products. Only medical supplies and other specialty items are still made with cotton only. Quilters love cotton and have come to depend on its strength, its flexibility, the way it responds to sewing, the way it presses, and frankly among other reasons, its beauty.

The real beauty begins when a farmer, whether he’s tilling the savannahs of Brazil, plowing the plains of Texas, or turning the river basins of China, plants a seed in the ground. That seed grows into an ugly, squat little plant, and eventually, once a year, a beautiful boll of white cotton will emerge. Fields of white, often as far as the eye can see.

In the 1600’s, the Japanese poet Matsuo Basho wrote: “A field of cotton – as if the moon had flowered.”

Once cotton matures, it is harvested and begins the first leg of its journey to a cotton gin. Next, ginned raw cotton is packed into huge bales and the majority of those bales will be readied for export. They travel to one of the world’s prolific weaving and spinning mills. Back during the 19th century, the United Kingdom was the center of the textile world, then in the 20th century the United States became the dominant player. Today, Asia has taken over that title.

It’s almost impossible to pick up a bolt of fabric, or a garment, and distinguish where all that cotton is grown, even if we know where the base textile was made. Most often, huge bales of raw ginned cotton are spread across the spinning room floor and giant machines blend fibers of different strengths and staple lengths, creating a veritable cornucopia of fibers from every growing region around the globe. From there, a yarn is spun and a textile is formed.

For quilting cotton specifically, the fabric manufacturers most often employ textile printing mills located in Japan, Korea and China.

While researching my book, “Cotton & Indigo from Japan,” I focused on Japan and her textile printing mills. The most interesting, and perhaps confusing fact, is that for the majority of textiles printed in Japan, the base textile is not made in Japan. The base textile is most often imported from China, Pakistan, or India, or other Southeast Asian nations.

Japan began growing cotton 600 years ago. But today, this island nation no longer grows cotton on a large scale. Nonetheless, some base textiles are milled in Japan (with imported cotton) and occasionally Japanese fabric manufacturers will use these domestic textiles for special collections, or simply for high-end requirements. Yuwa Shoten and the ever popular Kokka both produce some fabrics where the textile is both made in Japan and printed in Japan. And this is important because it allows for total quality control over the entire process.

Regardless of the origin of the cotton or the base textile, Japan is considered the premier destination for printing the highest quality quilting fabric today.

For example, everyone loves Moda fabric, right? Interestingly, about 45 percent of all Moda fabric is printed in Japan, which accounts for the lovely finish and hand of many of Moda’s products. Cotton + Steel, another popular quilting cotton producer, prints 100% of their fabrics in Japan. The list goes on. Many fabric manufacturers make a conscious choice of Japan because they want the best quality the market can offer.

No matter whether the fabric is printed in Japan or elsewhere, after the manufacturer produces bolts and bolts of their new fabric collections, those bolts are wrapped up and once again, the cotton fibers begin making the second half of their worldwide journey.

A seed goes in the ground --- it might be planted in some far flung local, or in soil right in your own community. It travels to a gin. Then it travels to some port, where it is placed on a ship. It is imported by a mill and made into some form of a base textile. Then, off it goes again to a printing mill. Its printed and finished into a brand-new fabric. Then, its packed up again. Trekked across nations and oceans. Finally, trains and trucks get this worldly cargo delivered right to your local shop.

Quite a journey for a wonderous fiber.

Ricky sat down with author Teresa Duryea Wong while at the Houston Quilt Festival and discussed the different types of Japanese fabrics that can currently be found in today's quilts. You might be surprised, it isn't all taupe and gray.

About the Author-

Teresa Duryea Wong is the author of two books on Japanese quilts and textiles: Japanese Contemporary Quilts and Quilters: The Story of an American Import (2015), and Cotton and Indigo from Japan (2017). She travels to Japan often to research and write, and travels the U.S. to lecture. She holds a Master in Liberal Studies from Rice University and in 2014, was named the 'Faith P. and Charles L. Bybee Scholar' by the Texas Quilt Museum and the Bybee Foundation. Teresa has been a quiltmaker for 20 years and she is also a handbag designer and makes handcrafted leather bags for her own label, mariejay.

.jpg)