1

1

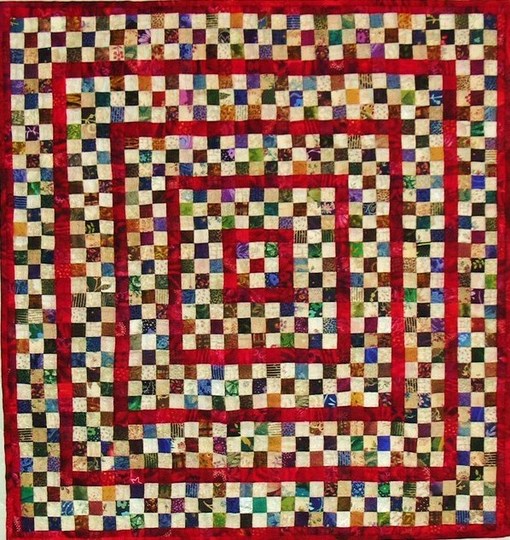

Feathered Star by TQS member Denise-nh

For the Love of Turkey Red

By Lilo Bowman

Can you imagine spending 25 days working at the most tedious and foul-smelling process just to obtain the color red for a piece of fabric? What is it about this particular color that captured the imagination, admiration, and envy of the world during the late 1800s?

In the 1880s, the range of colors available for fabrics was rather limited, and--due to the stress of washing (boiling and bleaching)--colors tended to fade fairly quickly. Typically colors were limited to available natural dyes or to the natural color of wool produced by animals. It must have been a thrill to add the luxury of a brilliant red fabric to one's quilt or wardrobe.

Turkey-red cloth was a highly prized cloth that was intensely rich in color that would not fade or bleed. The dyeing process, which employed the madder root and a host of other ingredients, originated in India, but soon spread to Levant, Smyrna, and Adrianople. The name Turkey red is often misinterpreted as a color, when it really is a dye process used in the region of the Middle East referred to at that time as Turkey. While the color of the fabric was a thing of beauty for the eye of the beholder, the process to produce this luscious material was far from it, and was held in secret for many years. Many spies were sent to this region of the world in search of the recipe.

It wasn't until 1765 that two Greek dyers from Smyrna were enticed to Rouen, France to demonstrate the technique for dyeing cotton and linen fabrics that would not fade or bleed after numerous washings and/or bleaching. This information subsequently was carried to Scotland, where--in less than 20 years--an entire industry revolving around the production of Turkey-red fabric developed in Leven, an area known for its production of quality textiles. Workers from all over Scotland and Ireland came to work in this booming industry.

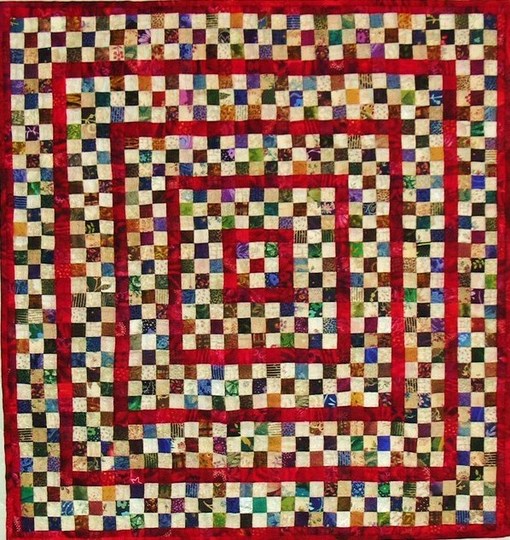

Red Squares by TQS member Charlotte

Alas, the process, or "craft" as it was called, was a very unpleasant job. The locals who worked the craft were known as "jellie eaters" (that is, jelly or jam) due to the red hands and arms they acquired from the dyeing process. As with most things during the 18th century, the manufacture of Turkey-red fabric was very labor extensive. It was also quite smelly! We found a recipe for the process from John Wilson's "An Essay on Light and Colours" (Manchester, 1786). As you can see, the process involved a multitude of steps, and could take as long as three weeks to complete.

1. Boil cotton in lye of Barilla or wood ash.

2. Wash and dry.

3. Steep in a liquour of Barilla ash or soda plus sheep's dung and rancid olive oil.

4. Rinse, let stand 12 hours, dry.

5. Repeat steps 3 & 4 three times.

6. Steep in a fresh liquor of Barilla ash or soda plus sheep's dung, olive oil and white argol.

7. Rinse and dry.

8. Repeat steps 6 & 7 three times.

9. Treat with a gall nut solution.

10. Wash and dry.

11. Repeat steps 9 & 10 once.

12. Treat with a solution of alum, or alum mixed with ashes and lead acetate.

13. Dry, wash, dry.

14. Madder once or twice with Turkey madder to which a little sheep's blood is

added.

15. Wash.

16. Boil in a lye made of soda ash or the dung liquor.

17. Wash and dry.

Keep in mind that this entire process was done without the aid of rubber gloves, facial masks, or good ventilation. (Can you image doing this yourself today? Not likely!) Many manufacturers soon discovered, however, that society loved the brightly colored and reliable fabric, and was willing to pay even 10 times more than for other fabrics. It was just that popular throughout the world.

Of course, then as now, printed designs were directed at particular tastes and markets. Muslims tended to prefer geometric and floral patterns, while Hindus desired elements such as elephants, peacocks, and tigers. Familiar circles, diamonds, and paisley can be found in a simple piece of fabric worn by beloved (and diverse) icons such as the cowboy and Benjamin Bunny, as well as by elegant ladies in European society. (We are talking here about the bandanna, which in Hindi means "to tie.")

So, the next time you go shopping for some luscious red fabric, remind yourself how lucky you are to be living in the 21st century. Your only problem now is coming up with the money to pay!

.jpg)